“It’s a borrowed term and we’re idiots to have accepted it.” This was the frank response from Indian actor Anupam Kher when asked about Bollywood in the new documentary, Brand Bollywood Downunder.

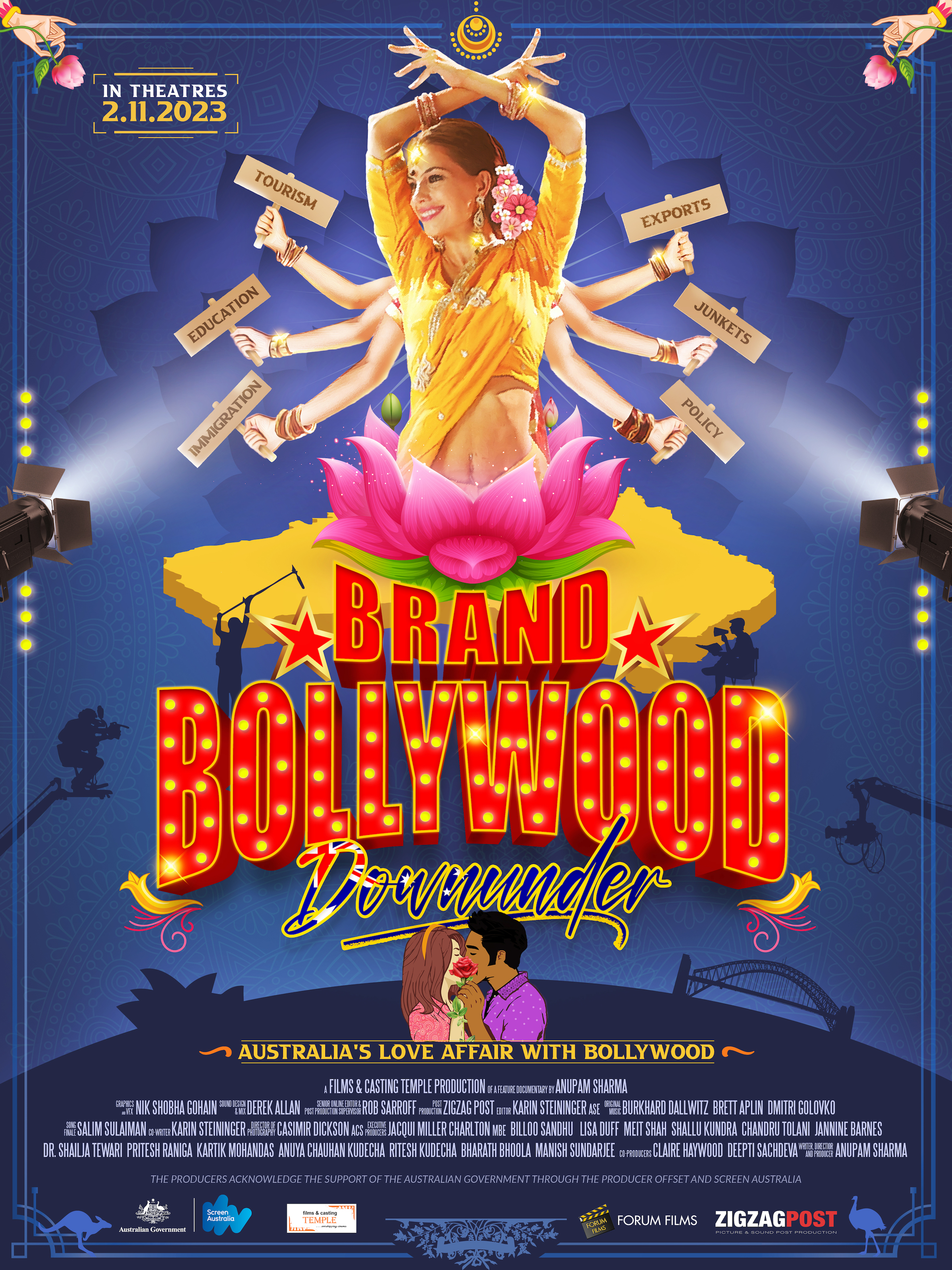

Bollywood, a term used widely to describe India’s multi-billion dollar Hindi-language film industry, has represented various things to people around the world. Entertainment, employment, education, escapism, empowerment, ego. The list goes on. But director Anupam Sharma uses this new documentary to try and set the record straight on what Bollywood is really about in the context of its relationship with Australia.

“For the last 20 years, [I can recall] the number of times I’ve been asked Australian or Western questions about Bollywood and why are there songs and dances – and they’ve all been answered in the film in a celebratory way,” Sharma told Draw Your Box. “So I hope I don't utter the word Bollywood for a while.”

Having been based in Australia for more than two decades, Indian-born Sharma has been instrumental in projects connecting India and Australia’s film industries, and is notably recognised by wider audiences for directing 2015 movie UNindian, starring Aussie cricketer Brett Lee and Indian actor Tannishtha Chatterjee.

In Brand Bollywood Downunder, he enlisted an impressive lineup of Bollywood heavyweights to speak about the globalisation of Hindi-language popular cinema through its “love affair” with Australia. These big names included Farhan Akhtar, Fardeen Khan, Harman Baweja and of course, Anupam Kher.

One of the key films discussed in the doco is Prem Aggan, a 1998 movie directed by Feroz Khan and starring the likes of Fardeen Khan and Anupam Kher. As one of the crew members himself, Sharma said the movie that was filmed in Sydney helped pave the way for more Bollywood productions to come to Australia.

“Prem Aggan started a craze,” said Sharma. “Dil Chahta Hai took it to a totally different level, and then Salaam Namaste was a key point, because it was touching upon a ‘story’,” he added, seemingly referring to the movie’s abortion storyline.

At the same time, Sharma noted, there were local Indian film festivals popping up in major cities, as well as Australian crews travelling to India.

“When Mr Rakesh Rohan did Koi… Mil Gaya, the alien creatures and visual effects were done by Australians,” said Sharma. “I would get a call from Aditya Chopra’s office – ‘Hey, we are doing Dhoom, India’s first motorcycle stunt film. Can we have some motorcycle riders because Australia is known for stunt riders thanks to Mad Max?’ So that was all happening.”

Amongst the synergies being established between the Indian and Australian film industries, there were also challenges faced by both countries in working together. Besides issues such as obtaining visas for Indian crews, there were also culture shock moments. Some Indians wondered why they couldn’t simply have a pop-up chai station on set with no occupational health and safety questions asked first.

“Why can't they buy yoghurt and food at 10pm, because all the restaurants shut at 8pm?” Sharma laughed.

Image Source: Supplied

It also took time for both countries to understand how one another approaches production.

“In India, as we say in the film, you have 20 people handling one light. In Australia, there are two people handling 100 lights,” explained Sharma, adding Aussies were also taken aback by how Indians worked.

“They [Australians] didn't realise how come these guys [Indians] can work without call sheets, schedules and scripts. And for me, it was very interesting because I was having it from both sides. The Australians were saying, ‘You're Australian, you know how it works’. And then the Indians were saying, ‘You're Indian, you know how it works’. So it was fascinating.

“But amidst all those conflicts, and amidst all the difficulties, the love for cinema from both sides won.”

So, what is Bollywood really about? What does it represent and what does it mean to those who create the movies, and those who watch them?

One of the guests in the doco nonchalantly claimed that especially in the early days, “Hindi films weren’t there to educate, empower or enlighten you, they were simply there to entertain”.

But for an industry that produces hundreds of films in a year with huge audiences around the world, doesn't it have a responsibility to interrogate important social and political issues?

“Bollywood will always take you on an escape,” said Sharma. “When Bollywood or cinema started to educate and enlighten people, then it was called the art film. It wasn’t called Bollywood anymore.”

The industry has slowly shifted over time. Sharma likened the diversity of Bollywood cinema to a “thali” boasting various dishes, but emphasised that dreaming and escapism will always be a fundamental element of Bollywood.

“I’m sure if you’re tired when you come home, you just put on a mind-numbing Sholay or Kuch Kuch Hota Hai. But if you’re really excited and energetic, then you’ll put on a film which discusses issues about India, LGBTQ rights and corruption. It’s like a thali,” he said. “You can pick and choose whatever you want to, but the escapist cinema still has that same important objective. It doesn't want to enlighten you. It doesn't want to educate you. It wants to purely entertain you.”

Both nations have spoken about a new co-production audiovisual treaty. As well as being a mechanism to facilitate more screen industry employment and cultural exchange, Sharma said it’s a gateway to helping tell the stories of the South Asian diaspora in Australia, especially the unique experiences of second-generation South Asians growing up between two cultures. Lion and UNindian are examples of this storytelling.

“Suddenly all of us realise, we don't have to wait for a call from India to help them with locations. We can create our own stories because kids who were born here have their own Australian stories, which are as diverse and as Australian as one can get… and this is when I say the Bend It Like Beckham’s from Australia started being made,” said Sharma.

“So what will the co-production treaty do? It makes telling those stories easier, by allowing me to hire a star writer from India or allowing me to hire staff. These are the kinds of things which will benefit apart from that,” he continued, before adding, “Our passion for sharing stories goes beyond any formal treaty and we will continue to make films whether it is with or without a treaty”.

Of course, Indian cinema is not limited to Bollywood. Many from the West, in particular, don’t realise that Bollywood is simply Hindi-language cinema. Other powerful Indian film industries create Telugu, Tamil, Kannada and Malayalam movies, to name a few. Ultimately, this documentary hones in on just Bollywood, and Sharma hopes audiences will learn more about the biz that has made household names of Shah Rukh Khan and Aishwarya Rai.

“I would like them [viewers] to know how and why in India they need and love cinema, and that they cannot pigeonhole Indian cinema into Bollywood, or all Indians into Bollywood fans.”

Brand Bollywood Downunder is now showing in select cinemas in Australia.